How cultural cringe spelled the end of Marvellous Melbourne buildings, and how locals eventually fought back

Documentary The Lost City of Melbourne tells a fascinating tale of a 1950s and ‘60s demolition spree in the name of progress, and how the city finally found its heritage voice. Director Gus Berger spoke with CBD News about his passion project.

In the first half of the 1950s, Melbourne was an anticipation-filled, even nervous city.

By 1956, it would be on show to the world with the Olympic Games in town, and like a proud mother hosting Christmas lunch, everything had to be perfect.

But in the lead-up to the games, there was a sense of unease about how the city might be viewed internationally, with the world’s cameras fixed on our backyard.

“From the early 20th century onwards, there was a bit of a feeling of embarrassment about Melbourne, on the part of Melburnians,” historian Robyn Annear explains in The Lost City of Melbourne documentary, which debuted at Melbourne International Film Festival in recent months.

“The feeling that Melbourne really was marvellous, which was part of 19th century Melbourne culture, had completely wilted by the 1950s.”

While it might seem absurd now, Victorian architecture at the time was, in fact, “really on the nose” according to Annear, and a cultural cringe began to permeate Melbourne.

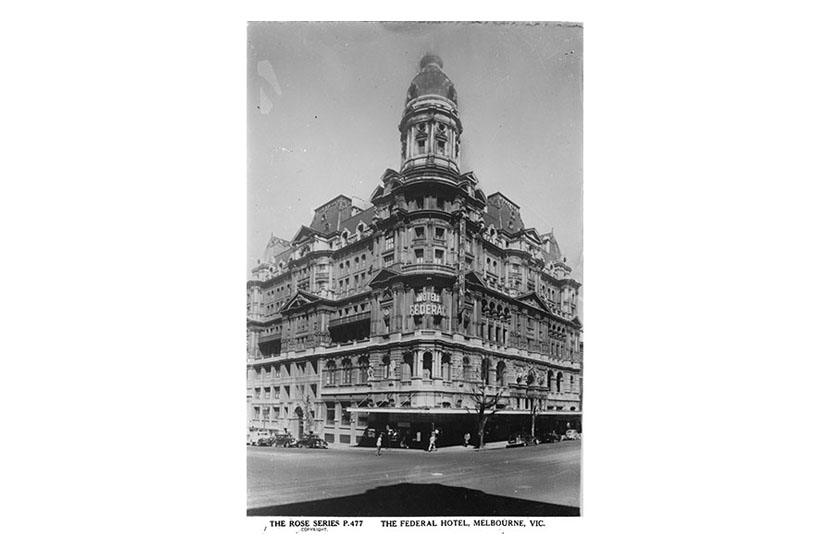

The city’s grand hotels like the Menzies and Federal — sans ensuites, creaking floorboards and all — were an “extreme embarrassment”.

“Progress was the rallying cry, it was a sign that we hadn’t progressed enough,” she said.

“Once the Olympics were over and Melbourne had kind of cringed, TV came on stream. Things like movies and magazine culture was really giving Australians an idea of what the rest of the world was looking like. We felt like country cousins by comparison.”

What followed was a period of rapid change, in the desire to progress and modernise.

Concrete, steel and glass were in, while things like cast-iron verandahs over footpaths were banned.

A few years following the Olympics, building height limits were removed, and a demolition spree of iconic buildings began.

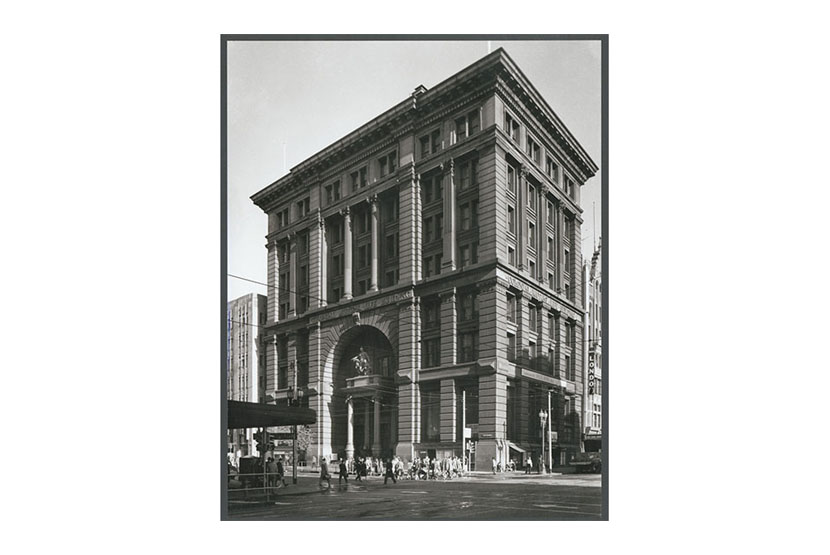

One of these, the Colonial Mutual building on Collins St, was demolished by “Whelan the Wreckers”.

When constructed, the building was “meant to last as long as the pyramids”, and the now famous company’s ability to successfully complete demolition in a heavily built-up area stamped their reputation in the city.

Whelan then became “part of the fabric of Melbourne, and seen as a sign of prosperity”, and their acrobatic and performative demolitions even became a “free show” for Melbournians.

It was this period of demolition and rapid change in Melbourne that prompted Thornbury Picture House owner Gus Berger to take a deep dive into what was a fascinating and sad time in the city’s history.

“I’ve lived in Melbourne all my life and [when looking at photography archives] was like ‘that building clearly doesn’t exist anymore — what happened to that? What happened to the APA building? Why isn’t the Federal Hotel still there?’. The story was always based on curiosity of what happened to these buildings,” he told CBD News.

“I remember thinking ‘why would buildings come down when we’re just about to have this big audience coming into Melbourne? And then there was this understanding of ‘oh right, Melbourne wasn’t modern enough’.”

Having previously made a short montage (shown during pre-show trailers) about lost cinemas and theatres in Melbourne (also a significant thread in the documentary), COVID lockdowns were the impetus for an even deeper delve into the history.

Familiar with accessing State Library of Victoria photographic archives, and how to find old film at the National Film and Sound archive, Berger was on his way.

“I mean, my God, no one could ever compensate me for the time I spent on it. But I think you can do that if you are interested and if you like that process. I found it really fascinating.”

After the wrecking spree of the 1950s and ‘60s, it wasn’t until the ‘70s that a preservation movement began to emerge: “In the ‘60s I think there was a feeling that there was too much being lost, but it was held by individuals on the street, or shopkeepers; people who probably thought they couldn’t do anything about it,” Berger said.

As the documentary details, it wasn’t until an iconic Melbourne theatre was almost demolished that people decided enough was enough.

“It wasn’t until we almost lost the Regent [Theatre] to make way for that big city square that was planned by the Melbourne City Council that people said ‘hang on a minute, this is going too far — you’ve just knocked down this massive building that’s taken out arcades and many odd shops, you can’t continue and take out the Regent, I used to go there with family’ etc. Everyone had these stories … that was the last straw, a line in the sand. Once the unions got involved and put a green ban on it, and local businesses and people and old cinema workers, they all bandied together.”

“So, then they probably realised that people had a voice and a say in what was going on. People started to realise something needed to be done, and I think the Regent was a catalyst for that.”

By 1974 a new act for protection of historic buildings was introduced — the first legislation in Australia to control privately owned historic buildings.

Through his research, Berger was surprised that the heritage movement did not start until around this time.

“I was definitely shocked at how late that came, but jeez, I’m glad it came because I think that it [demolition] would’ve continued, and it might’ve continued for another 10 years. And in those 10 years we could’ve lost the Capitol, or the Forum, or the Manchester Unity — you don’t know what else could’ve gone because nothing else was protected up until the ‘70s when they finally had some proper legislation.”

At the end of the film, historian Graeme Davison ponders whether he viewed things glass-half-full or half-empty.

“We’ve retained far more of our Victorian and early 20th century buildings than most cities in the world … sure, there are many things that have been lost, and there are many modern buildings that don’t really stack up. But nonetheless, I think I can tell the story of Melbourne by looking at its buildings. There’s enough there of the city that we inherited, to make us feel that we still inhabit a city that is recognisably Marvellous Melbourne.”

Berger agrees and is grateful for the incredible buildings that remain.

However, citing the mostly demolished Palace Theatre, he said there was no reason “why we should be complacent”.

“Nothing is 100 per cent safe.” •

Caption: The Lost City of Melbourne director Gus Berger

Caption: The Colonial Mutual building, demolished in 1960 (picture by Wolfgang Sievers, courtesy State Library Victoria).

Caption: Collins Street, as seen in the documentary (courtesy State Library Victoria).

Caption: The Federal Hotel (courtesy State Library Victoria).

City of Melbourne unveils next urban forest plan for the CBD

Download the Latest Edition

Download the Latest Edition