Leading architect pushes case to “re-life” CBD towers

A partner at leading firm Fender Katsalidis has outlined ways to encourage “the adaptive reuse of our cities’ ageing assets”.

A leading architect has encouraged an alliance between developers, designers and government to ensure more city buildings were given a second life rather than demolished.

Fender Katsalidis partner Nicky Drobis, a strong proponent of the “adaptive reuse” of buildings, said industry and policymakers working together was crucial to cutting down the “waste and carbon emissions associated with a new build”.

Research has suggested that the carbon cost of developing a typical commercial office building was worth up to 42 years of its operational emissions.

In recent times the City of Melbourne has made a clear point of preferencing retrofitted rather than new buildings in planning decisions.

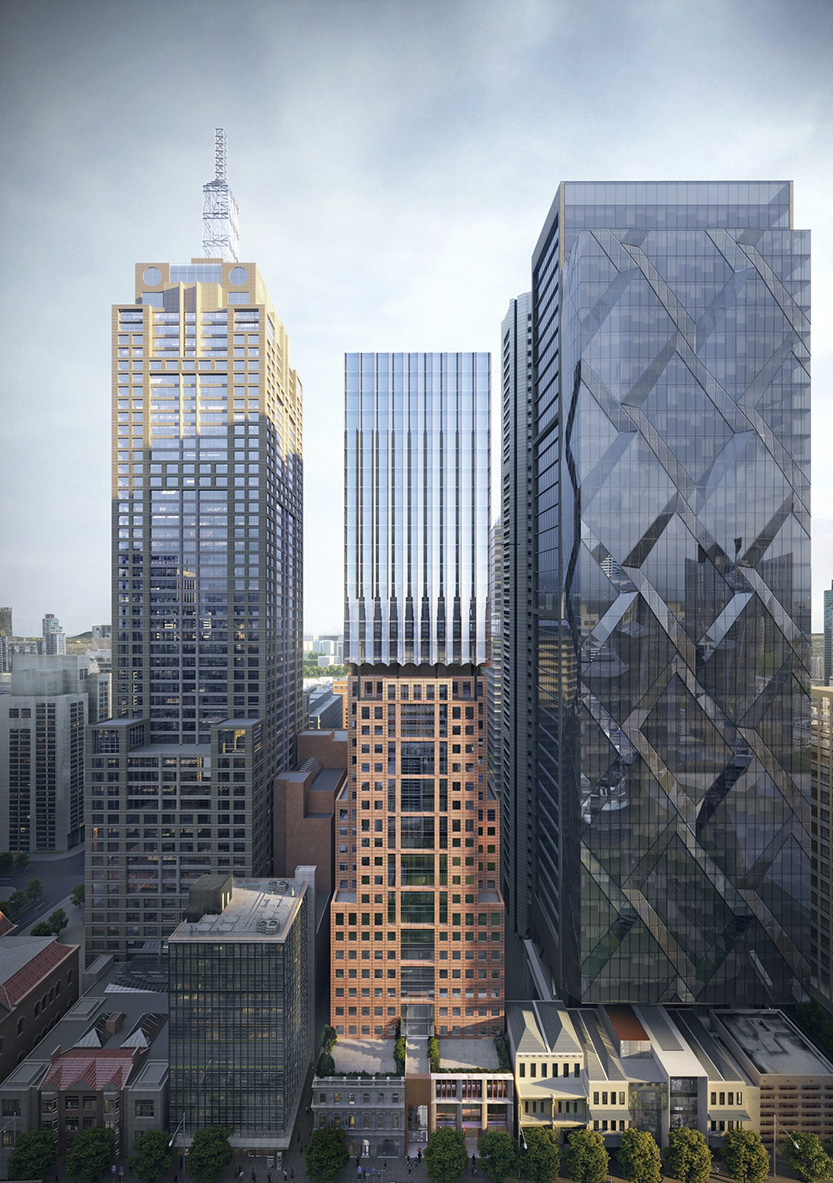

Ms Drobis played a role in recent plans that avoided demolishing a building at the Paris End of Collins St, instead opting to retrofit 17 storeys of “premium office space” above an existing 1980s-built commercial building with 1870s-built heritage-listed residential terraces at the ground level.

Developer Mirvac said the choice to “re-life” the building at 90-98 Collins St would save the equivalent annual carbon footprint of 889 Australian homes, drawing City of Melbourne commendation when it approved the project in February.

Now, Ms Drobis has released what she believes are the key factors to accelerating the adoption of adaptive reuse projects, not just for aesthetic and historical buildings, but for average CBD buildings.

“To date, the industry has been much faster to embrace the adaptive reuse approach for historically significant, and architecturally beautiful, buildings,” she said.

“However, this should further extend to ‘re-lifing’ buildings that have simply reached the end of their lifespan … we need to think more deeply about what the best urban outcomes are, and inevitably, those outcomes are all irrevocably tied to the reduction of carbon emissions and the increased well-being of citizens and the environment.”

Ms Drobis said a key challenge which hindered the adaptive reuse approach was that demolishing buildings was often a cheaper option for developers, so there needed to be “incentives for going the extra mile”.

This could include certain planning scheme tweaks.

“Currently, Melbourne has very stringent plot ratio and setback controls, so it could be worthwhile to start to reassess how those rules should apply if you’re retaining a building rather than starting from scratch.”

She also encouraged “flexibility” around floor space and building heights as a way to further incentivise developers to get on board.

“Increased allowances will redetermine how many re-life projects can go ahead, and help the city meet its environmental targets. With a shared goal for highly sustainable outcomes, and the right initiatives to make these projects a reality, we can correct the mistakes of the past and improve our built environment with biophilic design, comfortable floor plates and efficient ventilation.”

Ms Drobis also pointed to the importance of government policy to increasing re-life projects, referencing the City of Melbourne’s “Zero Carbon Building Plan” which was expected to go before the council later this year.

A late-2022 discussion paper informing the plan revealed that the current rate of local buildings being decarbonised per year was nowhere near that required for the City of Melbourne to reach its commitment of net zero emissions by 2040.

The report stated that for the council to reach its net zero goal, approximately 77 buildings would need to undergo a “deep energy retrofit” per annum, which was “significantly higher” than the current level.

Council endorses office tower at Flinders Lane despite querying car park demolition

Download the Latest Edition

Download the Latest Edition